We stand on the brink of an era where AI not only challenges us to work differently but also to think differently. Ethics is not a brake; it is a guide. In an earlier blog, we explored how Europe, the US, and China strategically approach AI and the values central to each. We concluded that AI itself is not the problem — it holds up a mirror to us. This blog goes one step further: why redesigning our systems is not a luxury, but an urgent necessity.

1. The source of innovation

Generative AI has spread rapidly, much as Everett Rogers once described in his diffusion theory — not through policy or technical measures, but through social behavior and perceived value. What began in the niche of tech developers was quickly embraced by a broad public. Citizens, students, entrepreneurs, and educators discovered for themselves how powerful and helpful AI can be — as a conversation partner, text writer, explainer, or thinking aid. Without advertisements, clickbait, or the flashing noise of commercial search engines. In Clayton Christensen’s terms, this is a classic disruptive innovation: simple, directly usable, and just good enough to displace the existing alternatives (endless searching, sifting through answers, clicking, reading, and starting over).

The speed with which generative AI spread shows how innovations often grow bottom-up in practice: not because power structures impose them, but because people see their value. What started as a technological niche is now becoming a societal habit. The question is no longer whether people want to use AI. The question is: are our institutions ready to adapt?

2. Discomfort with digital systems among citizens, consumers, and small businesses

Long before the rise of generative AI, there was already growing discomfort with the way digitalization was infiltrating daily life. What was originally intended to make processes simpler, faster, and cheaper increasingly feels to many like a source of frustration and alienation. Citizens get lost in government portals, encounter inaccessible interfaces, or get stuck in decision trees and chatbots seemingly designed to avoid personal contact. Consumers and small businesses recognize the pattern too: inefficient client portals, poor system integrations, and IT solutions that cause more work and costs than they save.

Sectors such as financial services, energy, and healthcare face increasingly complex regulations, often driven by major societal challenges — the aftermath of financial crises, pandemics, climate goals, housing shortages, and migration pressures. What started as crisis measures has evolved into a regime of control and regulation. Legislation is penetrating deeply into the behavior of individuals and organizations, spawning endless new obligations, systems, and audits. At the same time, the call for customization and a human-centered approach grows louder — a promise that sounds appealing but is increasingly difficult to fulfill.

This has led to a system with another fundamental flaw: the promised efficiency has not resulted in lower costs — quite the opposite. Public services have often become more expensive and more complex. Despite significant investments in technological innovation, citizens and consumers rarely experience better or faster service. Instead of systems adapting to people, people are expected to adapt to systems.

Digitalization thus does not feel supportive but coercive. It is not designed from human needs but from a logic of control and scalability, with “customization” as a thin veneer. This is exactly where distrust emerges: not against technology itself, but against the way technology is deployed.

3. AI and the role of the ideals of freedom and control

This growing discomfort with digitalization raises a fundamental question: what ideals drive our choices? In the debate about digitalization and AI, two underlying ideals — rarely made explicit — are crucial for how we deploy technology: the ideal of freedom and the ideal of control.

The ideal of freedom assumes trust, autonomy, and choice. Technology is then seen as a means to empower people: enabling them to make their own decisions, access knowledge, express themselves, learn, and participate. Generative AI fits this ideal seamlessly: it enables individuals to understand complex information, shape ideas, and navigate bureaucracy or learning materials more quickly. The success of AI among citizens stems from this promise of empowerment — technology adapting to the user, not the other way around.

In contrast, the ideal of control, often embraced by bureaucracies, views technology as a tool to minimize risks, standardize processes, and steer behavior. This ideal dominates many institutional AI applications: algorithms for risk selection, fraud detection, predictive models, citizen surveillance, and consumer influence through global tracking. Here, the focus is not the citizen or consumer, but the system — and the desire to make it as efficient, predictable, governable, and manageable as possible.

AI inevitably brings these two ideals into conflict. Where citizens embrace AI as a technology of freedom, it is often embedded within government and corporate structures in a logic of control. This highlights the risk that AI does not bridge the gap between citizens and systems, but rather exacerbates the tension.

The fundamental question is therefore not just how we deploy AI, but: what vision of humanity underpins it? Do we see people as autonomous actors — or as risks to be managed? Are we designing systems that expand choice — or systems that correct deviations?

4. Open norms and the utopia of customization

AI not only holds up a mirror to us — it also forces us to fundamentally redesign our systems. In many high-trust societies, laws, regulations, and agreements are deliberately formulated openly. They provide professionals — doctors, judges, regulators — with room to exercise wise judgment in individual cases. This space is based on trust in expertise, often safeguarded through disciplinary law or professional ethics. Supervisory authorities can also determine independently which issues to prioritize. This fits a high-trust society where professionals have the time and mandate to do what is right.

But the promise of customization is under pressure. When demand and supply become unbalanced, waiting times increase, or decisions become opaque, doubts arise. Citizens start asking for whom the rules are actually made, who controls the decisions, and from what worldview they arise. Who checks whether a professional’s judgment is still fair, recognizable, and explainable? And what underlying agendas drive decisions?

The openness that was marketed as the “human dimension” can turn into opacity, arbitrariness, and mistrust in professionals themselves. Judges who focus more on procedural refinement than clarity, regulators who prioritize internal games and prestige over public interest — these erode trust. And this is precisely where generative AI’s appeal grows: the desire for quicker, more transparent, consistent, and cost-effective judgments. Yet AI and open norms are uneasy companions. How do you combine algorithmic logic with context sensitivity, empathy, and situational judgment? The ideal of customization demands more than technology — it requires a rethinking of how we organize trust in a digital age.

Better explanations alone are not enough. It also calls for codifying more decisions and limiting the discretionary space of experts who stand above the parties. Where there is still room for professional judgment today, pressure grows to exchange it for predictability upfront, transparency during the process, and explainability afterward for citizens.

5. Practical example: AI to simplify access to public services

Applying for government support — whether for healthcare, housing, social assistance, or disability services — is often a frustrating experience for citizens worldwide. Application processes frequently involve multiple layers of bureaucrats, intermediaries, advisors, and specialists, leading to high administrative costs and a sense of helplessness among applicants.

How redesign and AI could improve such systems:

- Citizen-centered design: Individuals could securely share data from trusted healthcare providers via a Personal Health Record (PHR), allowing AI to advise on eligibility based on medical or personal circumstances.

- Process simplification: AI could interpret family composition or housing conditions (e.g., through video analysis or standardized intake forms) to proactively identify potential challenges and appropriate services.

- Cost reduction: By reusing verified information, administrative burdens could be dramatically lowered, providing faster, more objective, and more accessible application processes.

Lessons for system redesign:

- Transparency and trust: AI can reduce human bias but requires medical or professional review in cases of doubt and regular sampling audits to ensure fairness.

- Ethics as foundation, not afterthought: Systems should be designed around citizen needs, not bureaucratic convenience.

- Redistributing power: AI should not replace human officials but support them to achieve fairer outcomes.

Governments should approach changes systemically, bringing together legal, technological, and professional expertise to prepare for larger structural transformations.

6. Redesign and renewal — Time to put the citizen first again

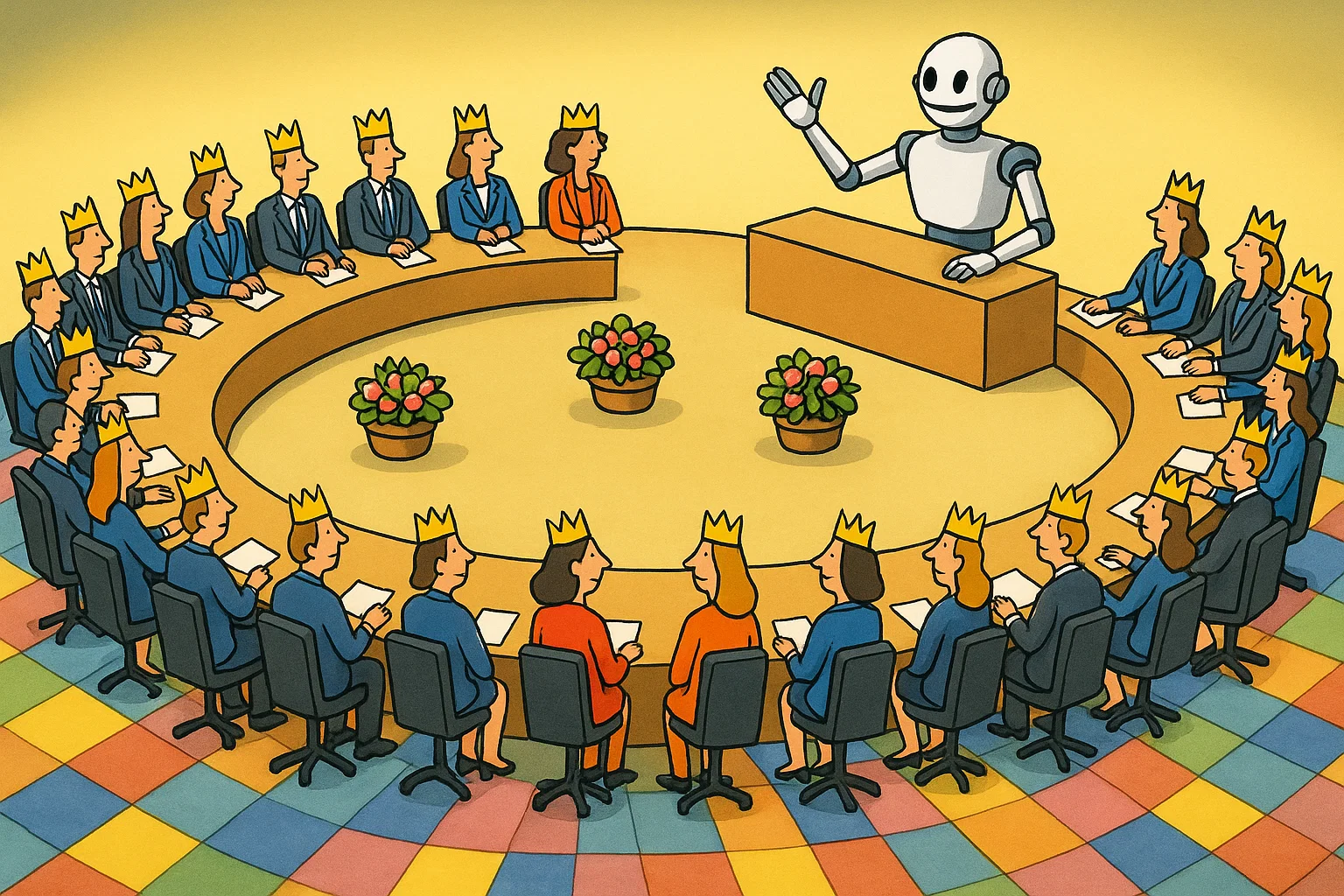

AI forces us not just to work differently, but to design differently. Not by simply making existing systems smarter, but by fundamentally rethinking structures — aimed at strengthening the position of citizens instead of protecting existing interests.

Practice shows the way. Public sector cases illustrate that redesign is possible: with AI, we can simplify bureaucracy, restore the human dimension, and return resources to where they belong — with the citizen.

But redesign requires courage. Courage to curtail the power of entrenched institutions in favor of citizens. Courage not to patch systems, but to radically redesign them. Courage to make ethics the starting point of innovation rather than an afterthought.

While AI can contribute to faster and more consistent decisions, redesign also requires balance. We must leverage the benefits of standardization — where predictability and transparency are needed — while preserving room for human insight and exceptions — where context and empathy are essential. Technology can achieve much, but sensitivity to context and moral judgment remain difficult to capture in algorithms. Redesign, therefore, does not mean choosing between rules or flexibility, but consciously combining them: standardization and the human dimension, depending on what the situation demands.

The challenge sounds simple but demands leadership: will we continue to tinker with systems that alienate citizens, or will we have the courage to redesign around trust, freedom, and human dignity?